The infatuation that the three Khan teenagers, born and raised just outside of Chicago, felt for the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in the summer of 2014 was hard to square with their upbringing.

Their parents had come to the United States from India as college students and viewed the country as “paradise.” They had attended Islamic schools but grew up playing basketball, watching CSI and the Walking Dead, and reading Marvel comics. When Kim Kardashian came to town, the oldest, Hamzah, took a selfie with her.

Yet, just after morning prayers, on September 14, 2014, Hamzah Khan, his brother, Khalid, and sister, Mina, wrote goodbye letters to their parents and set off for O’Hare where connecting flights and a fixer would ultimately drop them in ISIS-held Syria. They never made it; U.S. Customs and Border Protection stopped them at the gate, then took Hamzah to jail.

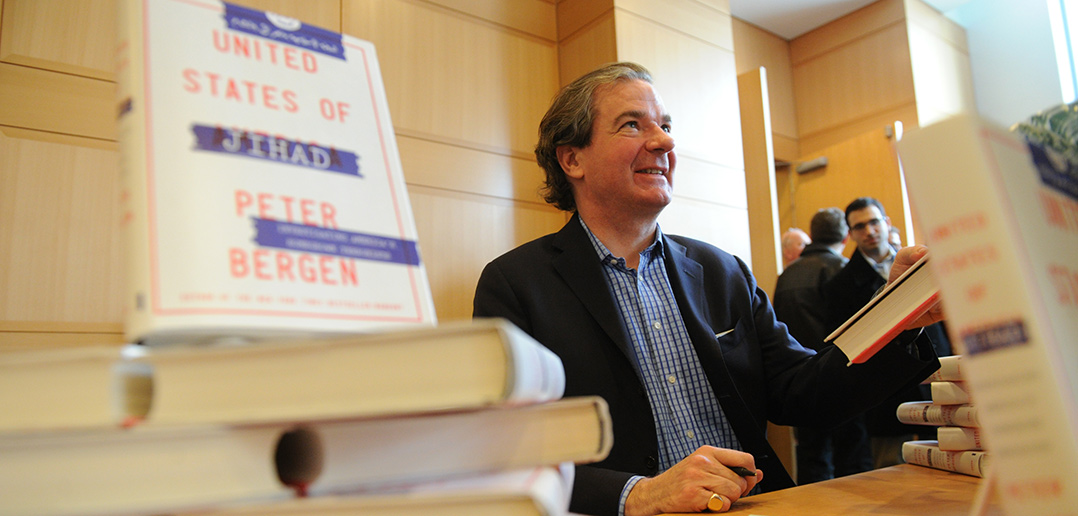

“It’s common to many ideologies that history has a direction and a purpose, and that the end point is utopia,” journalist Peter Bergen told a Center on National Security audience of more than 100 on February 12. Bergen was at Fordham to speak about the Khans and the other subjects of his new book United States of Jihad: Investigation America’s Homegrown Terrorists. “Hamzah Khan seemed more motivated by the desire to join ISIS’s ‘perfect’ Islamic state than the prospect of fighting in ISIS’s overseas campaign.”

In United States of Jihad, Bergen, CNN’s national security analyst and the author of four other books on terrorism, has attempted to grasp not only the reasons some Americans turn to jihadism but also the ways the fear of terrorism has changed American society and forced government institutions to respond.

“Peter Bergen’s new book offers students a chance to consider the complex world of terrorism cases in the United States, the way in which individuals are drawn to jihadist terrorism, and the relatively small number of terrorist events in the U.S. since 9/11,” said Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security. “His work is comprehensive, sobering, and free of the partisan dimension that marks most studies and conjectures about today’s terrorism.”

According to Bergen, who serves as a fellow for the center, “homegrown” terrorism has a long history in the United States—the 1970s were the “golden age” of terrorism, he said—but the 9/11 attacks raised the collective fear to a fever pitch not before seen in modern times.

On the day before Bergen’s talk, a Minnesota man pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to provide material support and resources to ISIS, drawn to the idea of fighting overseas to create an Islamic caliphate. Abdirizak Mohamed Warsame, who learned about Islam from YouTube videos of Anwar al-Awlaki, the American imam who joined al-Qaida and was killed in 2011 by a targeted drone strike, faces 15 years in federal prison but will likely join a nascent de-radicalization program created by a group called Heartland Democracy in Minnesota, a state which U.S. attorneys have said poses “an ongoing problem.”

For his part, Bergen was unconvinced that anti-radicalization programs work.

“U.S. government has a kiss of death problem with counter-radicalization; it’s a nebulous task to turn back that tide once it’s begun,” Bergen told Greenberg. “And trying to stop radicalization is a fool’s errand the government is never going to achieve. What it wants to do is stop recruitments.”

Indeed, in the United States, law enforcement has redirected its efforts to preventing young fighters from joining ISIS abroad as well as from mounting attacks in the country, usually in the form of increasing arrests, CNS statistics show. To date, the Department of Justice charged 81 people in federal court with supporting ISIS, with three alleged associates of ISIS-plotters killed by the FBI. All these individuals belong to a wide swath of ethnic backgrounds, from African to Eastern European, with 81 percent holding U.S. citizenship and one-third converts to Islam.

“Law enforcement is not acting casually; it has been signaled by the public to do it. Obama’s national security policy has a lot of continuity with the Bush policy, except under Bush the U.S. committed one drone strike, while under Obama, it’s been 120, with the death toll at 3,000 people,” Bergen said. “Americans have got their knickers in a twist about this issue, and the defenses we have put up against that kind of attack are enormous—a Keynesian amount of money loaded on Washington because of this issue.

“The good news is that jihadist groups’ ability to do large-scale attacks is zero; the bad news is that jihadists are largely American and tough to deal with.”

The FBI’s pathway to violence identifies a multistage process—grievance, self-justification, research, preparation—through which a prospective jihadist generally moves before committing an act of violence. Circumstances called “inhibitors,” such as “family ties, financial resources, a good job, and religious beliefs” generally keep people from the pathway, but when inhibitors “topple like dominoes, with one inhibitor knocking over the next in a sequence of decline,” according to agency primers on jihadism, the likelihood of an attack escalates.

However, as the already long reach of the Internet stretches farther into the minds of susceptible individuals, a new generation of “English-speaking, Internet-savvy jihadists” is now just “a mouse click away,” Bergen writes in United States of Jihad. Social media, online magazines like al-Qaeda’s Inspire and ISIS’s Dabiq and the virtual jihadist community on YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter not only replay but also amplify the vituperative messages of terrorists such as al-Awlaki, profoundly affecting the lost souls of Bergen’s book.

In the end, Hamzah Khan pleaded guilty to one felony count of attempting to provide material support to a terrorist organization. After serving up to five years in prison, his deal requires 15 years of court supervision, including searches of his cellphone, email, and computer four times a month, “psychological and violent extremism counseling,” and 120 hours of community service each year.

“Al-Awlaki was hugely influential, and the fact that we killed him didn’t mean we killed his ideas. Yet, a constitutional law professor from the University of Chicago was very comfortable with killing him out of fear of another emerging,” Bergen said.

“There might be something worse than ISIS coming down the pike. They could join up with Al-Qaeda. The differences are not that great; it’s just matter of personalities.

“There’s no reason to make the same set of mistakes we’ve already made.”