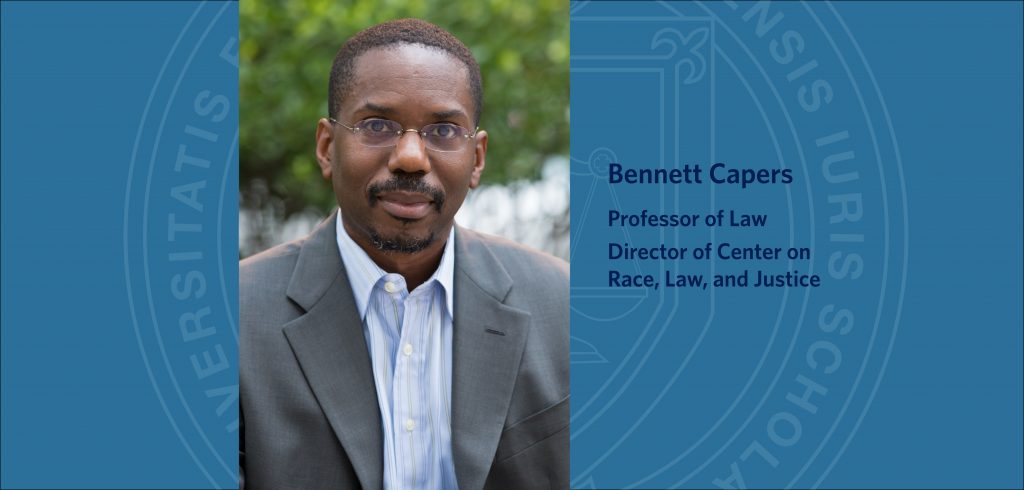

Professor Bennett Capers, director of the center on race, law and justice, was quoted in Slate in an article on the concept of police “testilying” and how it affects the criminal justice system.

The police reaction to George Floyd’s murder, as well as the resulting nationwide protests, introduced many Americans to the fact that law enforcement officers lie. After officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd, the Minneapolis Police Department issued a statement falsely claiming that Floyd “physically resisted officers” and excluding the fact that Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes. When Buffalo police officers violently shoved a peaceful 75-year-old man, their department falsely asserted that the victim “tripped and fell” during “a skirmish involving protesters.”

This tendency to lie pervades all police work, not just high-profile violence, and it has the power to ruin lives. Law enforcement officers lie so frequently—in affidavits, on post-incident paperwork, on the witness stand—that officers have coined a word for it: testilying. Judges and juries generally trust police officers, especially in the absence of footage disproving their testimony. As courts reopen and convene juries, many of the same officers now confronting protesters in the street will get back on the stand.

…

What would happen if a city really tried to eliminate testilying? I posed this question to Bennett Capers, a former federal prosecutor and Fordham Law professor who studies police lies. “In all honesty, I think my initial reaction would be that the system cannot exist without it,” he told me. “It would grind to a halt.” Capers said that “run of the mill policing would have to change. We are doing about 13 million misdemeanor arrests a year. With a lot of those small crimes, there’s fudging. Nobody’s paying attention.”