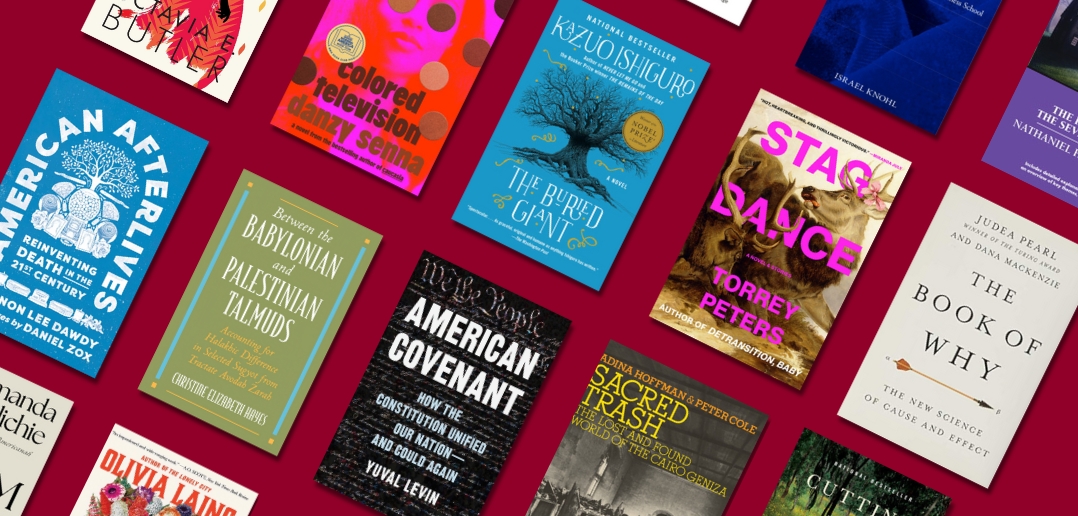

From thought-provoking science fiction and razor-sharp satire to a deep exploration of Talmudic history, discover your next summer read with these recommendations from Fordham Law faculty, who shared the books they’re most excited to dive into this season.

Bennett Capers

Associate Dean for Research, Stanley D. and Nikki Waxberg Chair, Professor of Law, and Director, Center on Race, Law and Justice

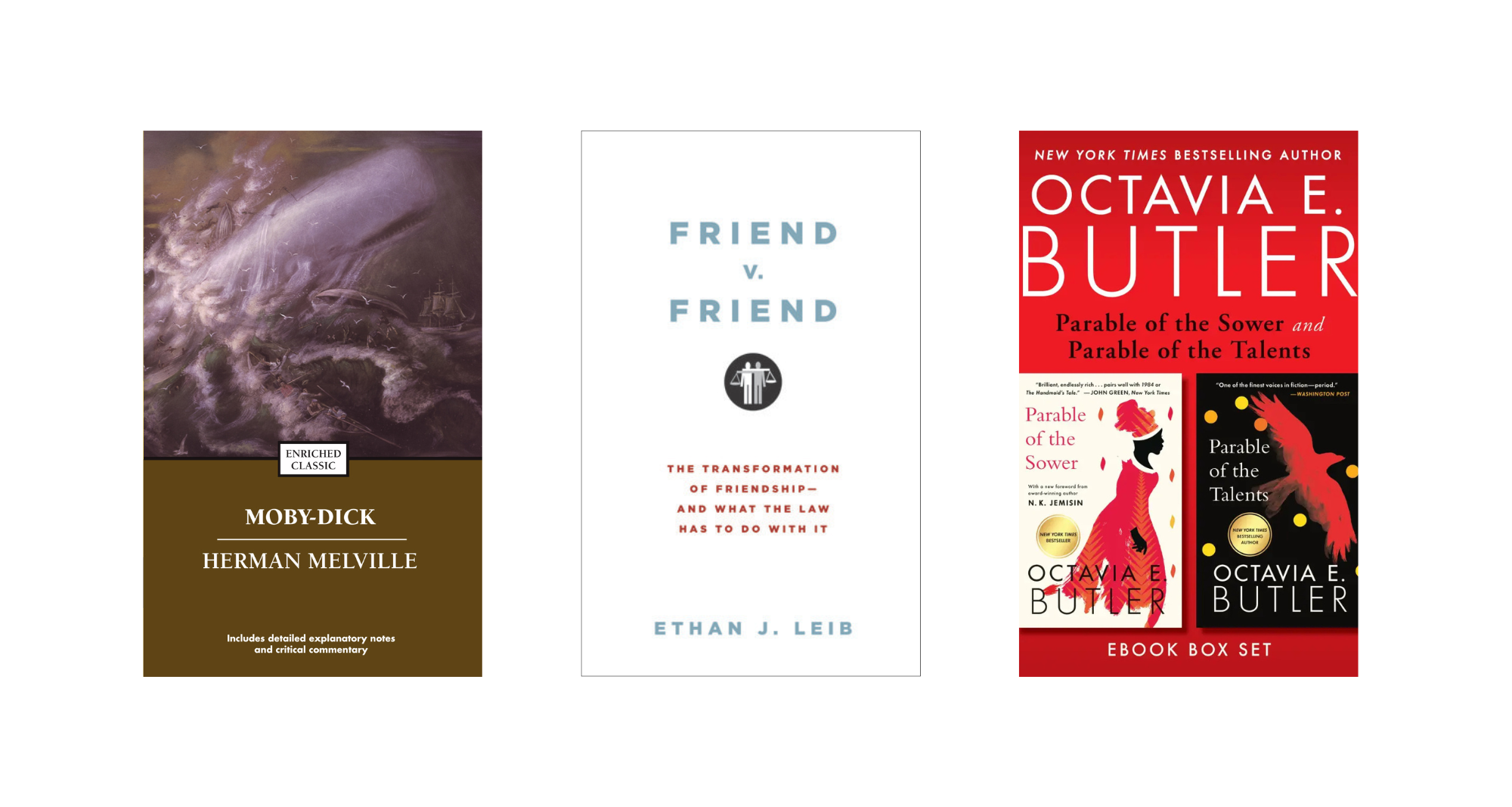

I’m a bibliophile through and through, and can hardly wait until summer to immerse myself in books. I have well over a dozen books on my “to read” list, so for now I’ll just mention three.

The first one is a book I last read over a decade ago, but want to read again: Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. (I’m partly motivated by the Met’s recent opera production of the story; but beyond that, Moby Dick is one of those novels that really stands up to re-readings. I’m also looking forward to re-reading Toni Morrison’s essay on Moby Dick when I’m done.).

The second book on my list is Friend v. Friend: The Transformation of Friendship—and What the Law Has to Do with It, by my colleague Ethan Leib. I skimmed it years ago, but it seems a good time to give it a close read. I’m especially looking forward to digging into his argument that the law gives friendship short shrift, and that this has negative consequences for society as a whole. (A sore point for me as an evidence scholar is evidentiary privileges, and the way we protect and valorize marital communications, but provide no protection for communications between best friends, the very people many of us are most likely to confide in.)

The third book on my list is actually a book series recommendation: Octavia Butler’s prescient novels Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents. Even though the novels were published in the 1990s, they really do read as if Butler foresaw the moment we’re in now, from politics to climate change, and wrote about it. Butler’s writings have had such an influence on my scholarship, especially my scholarship that engages in Afrofuturism and the law. But the reason I think others should read Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents is because, in the end, they are hopeful, and committed to the belief that change is possible.

Jennifer Gordon

John D. Feerick Chair, Professor of Law

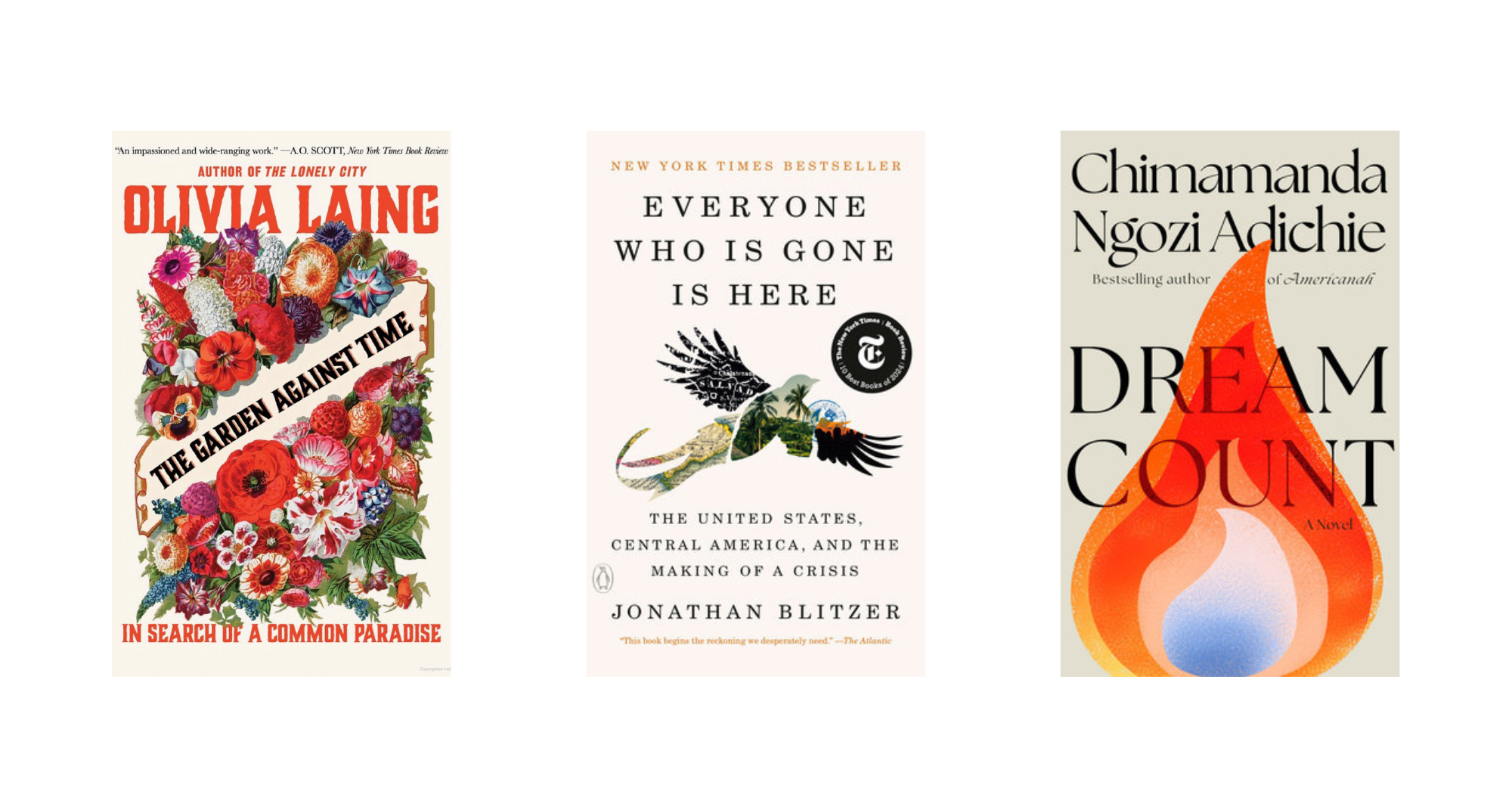

I have three favorite books I read this past year that I highly recommend: Olivia Laing’s The Garden Against Time, José Henrique Bortoluci’s What is Mine, and Jonathan Blitzer’s Everyone Here Is Gone.

In The Garden Against Time, Laing argues that the classic English garden and the British landscape are rooted in dislocation, environmental harm, and slavery, even as she describes her pleasure in planting an English garden of her own. I read this book last spring while a Fellow at Oxford, surrounded by beautiful gardens, and it created a healthy dose of cognitive dissonance. What is Mine is an extended essay in which Bortuluci, a Brazilian author, uses interviews with his father, a truck driver with cancer, as a starting point to grapple with the tensions between them in light of Brazil’s recent history. It is both deeply personal and politically insightful. Lastly, Blitzer’s Everyone Here Is Gone is an essential read to understand how U.S. immigration policy became increasingly punitive over the past 50 years, with Central America at the core of the story.

On my summer reading list is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dream Count. I’ve waited 12 years for a new novel from the author of Americanah, and I plan to savor every word.

Mariam Hinds

Clinical Associate Professor of Law, Criminal Defense Clinic Supervising Attorney

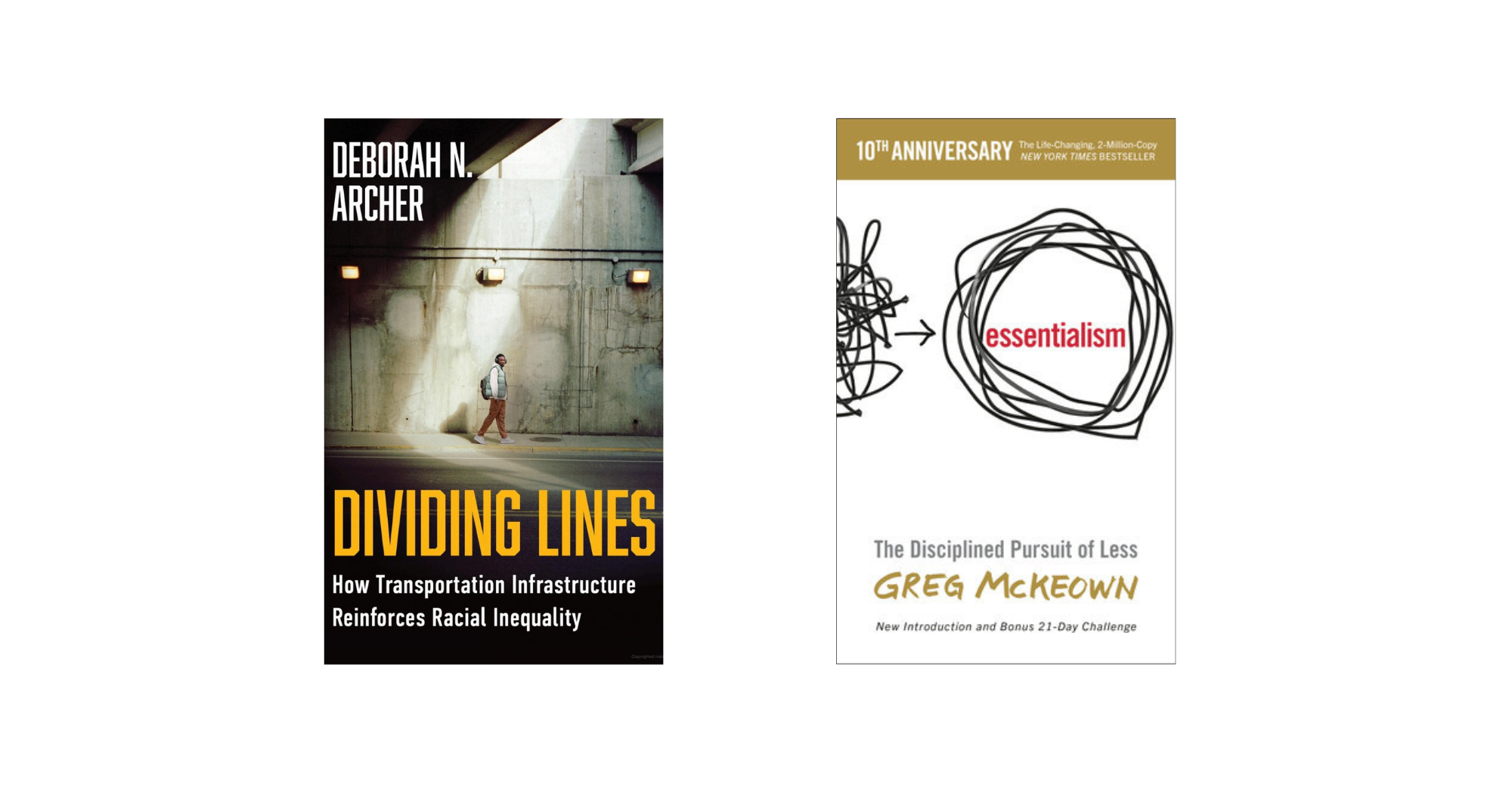

Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Greg McKeown is a seemingly radical take on time management that encourages a bit of ruthless prioritization. It encourages readers to align how they spend their time with their deeply held values by identifying their top priorities and discarding other, competing demands or tasks.

This summer, I am looking forward to reading Dividing Lines: How Transportation Infrastructure Reinforces Racial Inequality by Deborah N. Archer, an historical account of how infrastructure in the United States has perpetuated racial subordination, and I am eager to think critically about the potential overlap with and impact on crime, policing, and the criminal legal system.

Ela Leshem

Associate Professor of Law

The Tongue Set Free, by Elias Canetti, is a memoir that moves across cultures and languages in early 20-century Europe. Canetti has this sharp, vivid way of bringing the wonder of the author’s childhood back to life, as though it’s something we all experienced.

Peter Cole and Adina Hoffman’s Sacred Trash uncovers the stories and treasures of the Cairo Geniza, a medieval Jewish archive brimming with centuries of forgotten manuscripts—scripture, poems, letters, legal documents, and more. It recovers a lost mediterranean world with the grip of a detective story.

In American Afterlives, Shannon Lee Dawdy explores how contemporary Americans reimagine death rituals. It is funny, moving, and captivating all at once.

Ethan J. Leib

John D. Calamari Distinguished Professor of Law

I just finished and would recommend Israel Knohl’s The Sanctuary of Silence. You may have heard of the Documentary Hypothesis, proposing that the Five Books of Moses didn’t really come from Moses on Mount Sinai but are the collected works of the Yahwist (J), Elohist (E), Priestly (P), and the Deuteronomist (D). Knohl digs deeper into P and some of the tensions in that material. Sometimes Aaron and his sons seem to dominate the social hierarchy; other times, Israel is a nation of priests. Knohl traces two strains within P—one centered on the cult of the Temple and a later “Holiness School” that elevates the entire population. It is a stunning masterpiece.

Later this summer, when my Daf Yomi cycle (a commitment to study a folio of Talmud a day) hits Tractate Avodah Zarah, I plan to tackle Christine Hayes’s Between the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds. Hayes uses this particular Tractate as a case study to understand the relationships between the two Talmuds. Although most modern Talmudic study focuses on the authoritative Bablylonian, the Palestinian version—closed hundreds of years earlier—is a fascinating window into how an oral tradition was received over time. It reveals the authenticity of fragments in the Babylonian version while also showing interesting corruptions in later generations of rabbis, leading to questions about how creative the final redactors of the Babylonian Talmud might have been.

Aaron Saiger

Professor of Law

I’ve been assigning my 1L property students Chapter 1 of Austen’s Sense and Sensibility for many years. Last year, one of my Property students mentioned that George Eliot’s Middlemarch has a section called “The Dead Hand,” which is a key Property concept—and before I knew it, I wound up rereading all of Middlemarch. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s House of Seven Gables is the latest on my tour of property law in great novels of the 1800s. I’m particularly excited because it’s American. So far, I’ve looked only at the first chapter, and it alone, in addition to heirship and ownership, mentions surveying, mapmaking, government land grants, Indian displacement, changing cityscapes, and witchcraft.

Judge Douglas Ginsburg, for whom I clerked in 2000-01, just suggested to me that I read Yuval Levin’s new American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation—and Could Again. The reviews suggest that Levin has some optimism about the Republic, and I’m looking forward to seeing how he manages that.

Chinmayi J. Sharma

Associate Professor of Law

I recommend Catherine Lacey’s Biography of X and Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower because they are gorgeously written, fiercely creative explorations of identity, loss, and resilience, set in dystopian worlds that feel unsettlingly close to our own—making them especially resonant today. I also recommend Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, a brilliant novel that blends humor, surrealism, and political commentary to capture the absurdities of authoritarianism, fear, and moral compromise.

This summer, I’m looking forward to reading Abraham Verghese’s Cutting for Stone, a novel a friend recommended for its rich, complicated characters and the way it captures extraordinary lives unfolding quietly in overlooked corners of the world. I’m also excited to read The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro, one of my favorite authors, whose novels pull you so fully into his characters’ minds that by the end it’s hard to tell where they end and you begin.

Richard Squire

Alin J. Cameron Chair in Law, Fordham Corporate Law Center Faculty Director

This summer, I’m planning to read two books about history and architecture. The Old Way of Seeing, by Jonathan Hale, is a fascinating account of how the aesthetic sense in Western art and architecture has evolved over the centuries.

Universe of Stone by Philip Ball, explores the creation of Chartres Cathedral, considered by many to be the world’s finest example of Gothic cathedral architecture.

Julie Suk

Hon. Deborah A. Batts Distinguished Research Scholar, Professor of Law

The last novel I read is Colored Television by Danzy Senna, recommended by my friend and hero, retired Canadian Supreme Court Justice Rosalie Abella (and a distinguished visiting professor in 2022 at Fordham). It’s a laugh-out-loud, cringe-and-cry exploration of navigating the complex privileges and tragedies of racial hybridity in America, while trying to survive economically in a society too willing to rewrite those racial narratives for commercial gain.

Right now I am reading Adam Haslett’s Mothers and Sons. Haslett was my law school classmate, and he’s written a wrenching story of an immigration lawyer whose work on an asylum case for a young gay man triggers a confrontation of repressed memories from his own adolescence. Even if the depressing subject matter of immigration law is not a typical summer read, the writing is astoundingly good—and you will be drawn into these characters’ emotional journey.

This summer, I’m excited to read Han Kang’s We Do Not Part. It’s about a political uprising in the moment just before the Korean War. The novel was published in 2021 and translated into English in early 2025, just as South Korea was grappling with the aftermath of a president’s effort to declare military law, and the Constitutional Court’s decision to validate his impeachment. It’s always interesting to read a historical novel that may resonate with a present that the writer did not anticipate!

Maggie Wittlin

Associate Professor of Law

In a moment of peril for trans rights, you might think that the preeminent trans fiction writer of our time would try to appeal to the masses. But the collected stories in Torrey Peters’s Stag Dance could never be this stirring, this gutting, and this fun if she were playing it safe. Instead, her characters are often messy and cruel, and they have a lot of sex. But her fiction ultimately welcomes, rewards, and punishes all comers: For example, the collection’s centerpiece novella, in which a hulking lumberjack decides to go to a dance as a “skooch” (lumberjackese for “woman”), speaks to anyone who has felt frustration that the world does not see them the way they see themself.

This summer, I am planning to read The Book of Why, by Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie. I have been (slowly, haltingly) working on an article on causation in the law, and after reading countless law review articles and philosophy articles, it is high time that I read about the still-new science of causal inference. Judea Pearl, one of the founders of this field, immodestly-but-accurately notes that it has caused a “revolution” in our understanding of causation. But while this science has implications for epidemiology, economics, and computer science, is it useful for explaining causation in tort law? I’m skeptical but eager to take from it what I can.