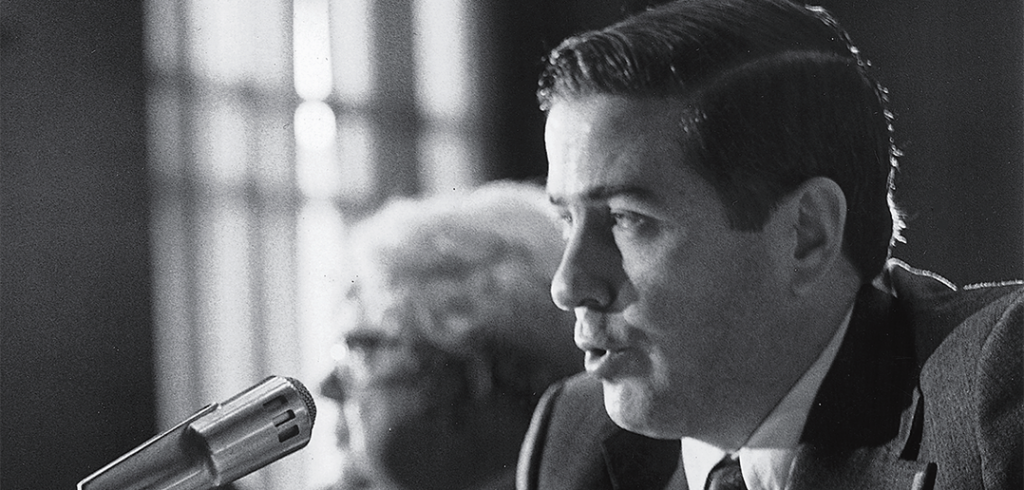

Dean Emeritus and Norris Professor of Law John D. Feerick’s new memoir, That Further Shore: A Memoir of Irish Roots and American Promise, spans his upbringing as the eldest child to Irish immigrants in the South Bronx to practicing law, his landmark role in framing the U.S. Constitution’s Twenty-Fifth Amendment, and his leadership as dean of Fordham Law School, among many other major milestones. To celebrate the launch of the book, Dean Feerick was recently joined in conversation by Dean Matthew Diller for a live-streamed event (watch the video).

In the following excerpt from That Further Shore, Dean Feerick reflects on his lifelong commitment to serving others:

The idea of serving others was instilled in me by Mom and Pop. As their oldest child, I was expected to show leadership in the family, which meant keeping an eye on my younger siblings. I played the same role in my neighborhood, where I often played with children who were younger than me. At times they looked to me for guidance and protection against neighborhood bullies. Back then I had a pretty fierce headlock move and sometimes had to use it, but the threat of doing so was often enough to smooth over the situation.

The idea of serving others was instilled in me by Mom and Pop. As their oldest child, I was expected to show leadership in the family, which meant keeping an eye on my younger siblings. I played the same role in my neighborhood, where I often played with children who were younger than me. At times they looked to me for guidance and protection against neighborhood bullies. Back then I had a pretty fierce headlock move and sometimes had to use it, but the threat of doing so was often enough to smooth over the situation.

When I went to college, I understood the necessity of working part-time to help Mom and Pop deal with the family’s finances, and opportunities to display responsibility in other contexts emerged.

My teachers influenced me in the way they cared for students, both in and out of the classroom. When I graduated from law school, I saw a life in the law as embracing a larger service, although what that meant wasn’t clear to me at the time. Fordham’s values didn’t emphasize making money as a life goal, nor did Mom and Pop, who lived simply and frugally, and I had no burning passion to accumulate wealth. I still recall my college classmate Bob Bradley saying that I had the potential to someday earn $40,000 a year, but I really didn’t know what that meant. I often thought in those years that if I could only make it to age 35, the age of Lawrence Reilly, a lawyer at a firm where I worked during law school who was my role model, and have a chance to repay Mom and Pop, my life would be complete. And so off I went, wet behind the ears and naïve about so many aspects of the world.

Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy, which I read in my third year of college, was a benchmark of sorts for me, helping me reflect on the meaning and purpose of my life through the views of many great thinkers. But as things turned out, I had an innate incapacity to choose and focus, thereby accepting all kinds of requests. As a lawyer for more than fifty-eight years, I must have spent nearly half of my time involved with some form of volunteer service (including my writings). My service activities have ranged from committees of bar associations, to government bodies, to not-for-profit and community organizations, to educational and religious institutions, to boards of public companies, to participation in politics, to service in other countries (Ireland and Ghana), and to helping individuals cope with personal challenges. It’s hard to find a common denominator, other than the model of a vocation of service presented to me by Mom and Pop, and the priests, Ursuline Sisters, and Marist Brothers who taught me.

I came to particularly enjoy service in the form of writing, in which I was able to advocate, educate, offer points of view, and honor others. In time, I’d write law review articles, books, book reviews, op-ed pieces, articles for encyclopedias and bar journals, bar association reports, testimony for legislative hearings, opinion letters, briefs, memoranda, and speeches, including eulogies, remarks for programs, and many hundreds of tributes to others on special occasions. The opportunity to speak positively about another person gave me particular joy. I sought to find in each person’s story their uniqueness, and I often found myself inspired by their example.

Politics, I would have thought, might have engaged me more fully, as in college I enjoyed the opportunity to serve students through student government positions. I believed that I might have some kind of political career, but the opportunities to be involved in constitutional reforms of our presidential system took me in another direction. I’m not sure I would have lasted long in elective politics anyway, given the attacks often associated with such participation, along with the need to raise enormous sums of money and the pressures and expectations associated with such fundraising—all of which has increased exponentially over the years.

My time at Fordham Law helped me understand the larger dimensions of a life as a lawyer. Dean William Hughes Mulligan and the small faculty he’d assembled challenged us to be good lawyers, and we understood that to include some form of public service. Service to our country was also inspired by the graduates who fought for the country in World War II and the Korean War, and by the requirement that we serve in the Armed Forces.

We also learned about the successes of graduates in the private practice of the law and in public life. I left Fordham with a desire to make the school, and Mom and Pop, proud and with the knowledge that the greatest success may be in the multiple ways we give back to the world in which we find ourselves.

Upon graduation, I joined Skadden, which, despite its small size and uncertain future back then, stressed the importance of service to the profession. I was on the job only a short while when Barry Garfinkel, a partner at Skadden, urged me to join the New York City Bar Association and become active in the association. I also became a member of the New York State Bar Association and the American Bar Association. Later, Skadden’s Joe Flom would encourage me and other lawyers at the firm to give back to the community through, for example, service on not-for-profit and community boards.

In these activities, I learned about the importance of serving our communities, cities, states, and country. I also became exposed to issues involving discrimination, oppression, and unfair treatment within the legal system. It was clear I had to do my part, and that doing so involved more than serving on a committee. Over the years I took on the representation of individuals in non-compensated settings and used various platforms to promote public service.

Without performing some type of public service, lawyers miss out on the full potential of their professional lives. There are so many opportunities available to represent people, to work in nonprofit and government offices, to advance the state of the law, and to teach and educate the next generation. Archibald Murray did so as the attorney in chief and executive director of the New York Legal Aid Society. Fordham Law graduates Malcolm Wilson, the fiftieth governor of New York, and Louis Lefkowitz, who served as attorney general of New York, did so through decades of service to the state. Former New York Court of Appeals Chief Judge Judith Kaye’s public service changed the justice landscape by effectuating jury reforms, establishing problem-solving community courts, enhancing access to justice for those unable to afford counsel, and increasing diversity in the courts. James Gill did so through his commitment to pro bono service for individuals in need of help, nonprofits requiring volunteers, government officials seeking active citizen engagement, and the causes of the Catholic Church and the schools that educated him. Law firms and corporate legal departments have also made impressive commitments to serving the underserved.

I have found the lawyers I know to be generous with their time in helping others through their knowledge of the law and their legal skills. Their services are often misunderstood or largely go unnoticed by the larger public. I became exposed to that tradition of service often at Skadden and because of my father-in-law, William Platt, who gave freely of his time to neighbors and strangers in Southampton. I tried to do my part, something that has brought me much happiness.