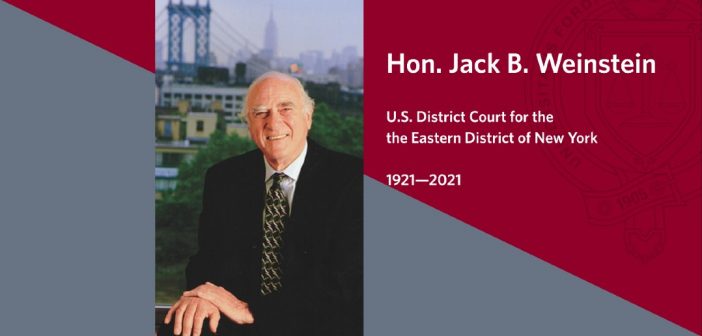

Judge Jack B. Weinstein, senior district judge for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, passed away on June 15 at the age of 99. He served on the court for more than 50 years, presiding over numerous high-profile and complex cases, including the Agent Orange class action.

In 2013, Fordham Law School awarded Judge Weinstein the Fordham-Stein Prize for his outstanding career as one of the most influential and renowned trial judges in the country while at the same time dedicating himself as a major scholar of the law. “It is particularly gratifying to receive this honor at Fordham Law School,” Judge Weinstein remarked in accepting the award. “So many of the lectures and seminars I attended here clarified the law. So many scholarly works written here have provided vital help to our court.” Noting the ties between the law, public service, and social work, he added: “Helping people requires more than the application of law. It needs empathy and concern—a human face and a human heart.” To further this connection, he founded the Evelyn and Jack Weinstein Fund for Law and Social Work, which supports scholarships in the fields of law and social work.

Judge Weinstein had a profound influence on many Fordham Law faculty members, among them Dean Emeritus Michael M. Martin and Professor Howard Erichson, who penned “Judge Jack Weinstein and the Allure of Antiproceduralism” for the DePaul Law Review in 2015. We asked Dean Emeritus Martin and Professor Erichson to share their reflections on Judge Weinstein’s life and jurisprudence.

A “Hero” on the Bench

Dean Emeritus Michael M. Martin:

I first encountered Judge Jack Weinstein in the fall of 1963 as an author of the casebook in my first-year civil procedure course—my favorite class in law school. I was impressed to learn then that he was not only a Columbia Law professor but also had served as county attorney for Nassau County from 1955 to 1957.

As a third-year law student, I had the privilege of helping edit an article he wrote for the Iowa Law Review [Weinstein, Judicial Notice and the Duty to Disclose Adverse Information, 51 Iowa L. Rev. 807 (1966)]. The breadth of his knowledge, the depth of his insight, and the clarity of his writing set him apart among the authors we published that year.

When the law of evidence became a specialty for me as a law professor, I was always Judge Weinstein’s student. His five-volume Weinstein’s Evidence was the go-to source for learning about the Federal Rules of Evidence, and the evidence chapters of Weinstein, Korn & Miller, New York Civil Practice served the same function for New York evidence law. Among the scholars we consulted, he probably had the greatest influence on my work when I served on committees drafting a proposed Code of Evidence for the State of New York (which was never enacted) and when I wrote the New York Evidence Handbook [1997, 2d ed. 2003, 3d ed. 2017] with Professor Dan Capra.

Likewise, I was Judge Weinstein’s student when teaching civil procedure and conflict of laws. His comprehensive writings on the subjects informed my knowledge and his imaginative approaches to procedure issues as a judge forced us all to think more deeply about purposes and principles.

Beyond his scholarship, what solidified Judge Weinstein’s position as my hero was the way he conducted himself as a judge. “Justice” was his watchword, and he put his prodigious intellect and creativity—as well as his compassion—to its service. I saw this on the periphery of the Agent Orange litigation where he tried against long odds to provide compensation for Vietnam veterans, as well as in countless press reports of other cases.

When I became dean I was surprised (actually, astounded) to realize that this giant of the law had not been honored with the Fordham-Stein Prize, which recognizes those who represent the highest ideals of our profession. I am pleased to say that that omission was rectified during my tenure. And because Superstorm Sandy required postponing the Stein Dinner, we had the pleasure of honoring Judge Weinstein at both a small dinner and the postponed gala dinner a year later.

Love, Wisdom, and Intelligence

Professor Howard Erichson:

Judge Weinstein played a critical role in multiple mass tort litigations, including tobacco, asbestos, and pharmaceutical cases. Each time, he fearlessly pursued aggregate justice—often pushing the envelope of what was permissible under existing law.

I recall one evening when I bumped into Judge Weinstein at an event. Knowing that I taught complex litigation, he casually mentioned that, earlier that day, he had certified a nationwide class action for punitive damages in the tobacco litigation. I stared at him incredulously and said, “You know the Second Circuit is going to reverse, right?” I can still picture his perfect, infectious smile and his knowing shrug.

Implicit in that smile was the judge’s understanding that, sometimes, to accomplish justice in intractable situations, a judge has to push boundaries and try approaches that have never been tried before—even at the risk of reversal.

I once wrote an article about Judge Weinstein’s “antiproceduralism”—that is, his willingness to play fast and loose with rules of procedure in order to achieve substantive justice. He was not a judge who would let technicalities stand in the way of achieving justice.

For a proceduralist like me, it can be uncomfortable to see a judge do this. But, the magic of Judge Weinstein was that—even when he stretched the rules of procedure—he did it with such love, wisdom, and intelligence. It made us want to forget the rules and just admire his sense of creativity and justice.

I’ve never seen another judge like him, and I doubt I ever will.