The trial of notorious mobster Charles “Lucky” Luciano and his associates not only captivated the public’s attention, but also took the legal world by storm in the late 1930s. It was the first time a mobster was convicted for crimes that involved racketeering.

Though Special Prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey took center stage during the trial, Eunice Hunton Carter ’32 played a critical role behind the scenes. She linked prostitution in the city to the work of Luciano, orchestrated the sting operation that resulted in Luciano’s arrest and imprisonment, and served as the only woman prosecutor and person of color on the Luciano trial.

Authors Marilyn S. Greenwald and Yun Li explore Carter’s life as well as her deep-rooted fight for social justice in the 20th century in their new book, Eunice Hunton Carter: A Lifelong Fight for Social Justice.

They believe Carter can serve as a role model for many people today, especially those who work to promote gender and racial equality.

“There are never enough stories about Black female pioneers,” Greenwald and Li said. “The one about Carter is particularly fascinating to us as this little-known and modest lawyer played a crucial role in convicting the nation’s most notorious mob boss in what was billed as the trial of the century.”

Through transcripts, letters, and other primary and secondary sources from archives in the United States and Canada, Greenwald and Li showcase how Carter continued the legacy of her family who valued education, perseverance, and hard work. Carter’s father William nearly single-handedly integrated the nation’s YMCAs in the Jim Crow South and was one of the first top Black administrators of the international YMCA. Her mother Addie provided aid to Black soldiers in France during World War I and became a leader in several global and domestic racial equality causes.

A Fordham Law Foundation

Carter, who was well known for her involvement in Harlem society, enrolled at Fordham Law in 1927 as an evening division student. This marked the fruition of her desire to study law, which dated back to age 8.

“Carter’s time at Fordham instilled in her the importance of understanding how attorneys can help improve society and her time there helped develop her sense of civic duty,” Greenwald and Li said.

Carter, while attending law school, was simultaneously working full-time in social work as a supervisor in the Harlem division of the Emergency Unemployment Relief Committee and taking care of her son, Lisle Jr., who had been ill.

Carter was one of the first Black women to earn a law degree at Fordham in 1932 and to pass the New York bar nearly a year later. After receiving her law degree, she opened a law office, was an attorney in private practice, and ran as a Republican candidate for New York’s Nineteenth Assembly District seat in 1934.

In 1935, Carter’s efficiency, diligence, and street smarts caught the eye of District Attorney William C. Dodge. She was named a New York assistant district attorney, mostly prosecuting prostitutes and abuse cases in New York City’s magistrate court.

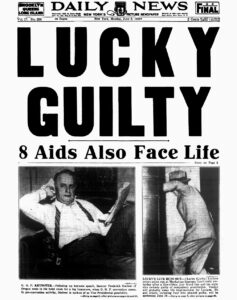

Daily News front page on June 8, 1936, announcing the verdict in the Luciano trial. (Photo: Courtesy of Marilyn S. Greenwald and Yun Li)

Being Part of the “Trial of the Century”

When Dewey asked Carter to work in his office in 1935, she was appointed a member of his “Twenty Against the Underworld” legal team—serving as the only woman and person of color on the special prosecution staff.

Carter spearheaded the investigation that proved the Italian mob ran New York City’s brothels after uncovering the link between attorneys, underworld figures, and prostitutes in New York City. Her warm and soft demeanor also helped flip witnesses who detailed Luciano’s behind-the-scenes involvement.

The mob kingpin was found guilty in 1936 and sentenced to 30 to 50 years in state prison. Luciano was released from prison and deported to Sicily, Italy, a decade later.

A Trailblazing Career

When Dewey was elected as one of New York County’s five district attorneys in December 1937, Carter remained on his staff. She went on to head the Abandonment and Special Sessions Bureaus—the largest bureau in the prosecutor’s office at the time, which handled misdemeanors in three different courts.

Eight years later, Carter left public employment and the prosecutor’s office and entered private practice in 1946. Two years later, she became business partners with journalist and businessman Ernest E. Johnson to form Carter-Johnson Associates, a public relations firm geared toward minorities and shared office space with her law firm.

Carter eventually became a legal advisor to the newly formed United Nations, a member of the U.S. National Council of Negro Women, secretary of the Mayor’s commission on conditions in Harlem, and several other national and global organizations.

Eunice Carter at home in 1942, near the photo of her son, Lisle. Jr. (Photo: Courtesy of Marilyn S. Greenwald and Yun Li)

Greenwald and Li hope that Carter’s story gives readers historical perspective on several eras and venues—including the Jim Crow South of the late 19th century where her father worked, the first two decades of the 20th century when women and people of color met prejudice and fought for rights that had long been held back, and the 1920s and 1930s when the mob gained a foothold in the United States.

“We hope that reading about Carter will introduce readers to one of history’s many under-studied and, frankly, under-appreciated figures,” they added.

“We tend to read about many of the same people over and over, and we sometimes don’t realize that many people, like Carter and her family, were pioneers who paved the way for many who came after them.”